Edited by Ken Redmore

Background

By the early years of the twentieth century almost all wheat, barley and oats on Lincolnshire farms were threshed by machine. Some of the larger farms had a fixed thresher installed in the barn, perhaps once operated by horse power, but the majority were reliant on a portable threshing machine powered by steam traction engine and brought to site by a contractor.

Threshing grain took place largely in the autumn and winter, with all but the smallest farms receiving visits from the contractor on more than one occasion in this period. Most farmers needed to have some of their wheat threshed early in the autumn so that good straw was available for thatching stacks and covering potato clamps before the onset of winter weather. Seed corn – especially wheat – was also needed for autumn sowing. At other times farmers tried to take advantage of favourable market conditions and be in a position to sell their freshly threshed grain.

The threshing contractor also threshed or hulled clover and grass seed; other crops such as mustard and beans could also be threshed on the farm by machine. While special threshers were available for dealing with these other crops, many contractors could adapt their machines by inserting riddles and sieves of different mesh sizes and modifying the air blast.

Chaff cutting was also carried out by some threshing contractors, though smaller farms were likely to rely on hand-operated cutters. This involved chopping barley and oats straw into short lengths for an addition to horse and cattle feed to ‘bulk it out’. It had little nutritional value but was an essential part of the daily diet for working horses. The contractor’s chaff cutter was powered by his traction engine and incorporated a blower which delivered the cut material directly into an adjacent farm building through a window opening or door. Some contractors at this time also had straw trussers or baling presses which compressed and packed loose straw from the threshing machine, thus making it easier to store.

Moving the threshing set from farm to farm was a slow and laborious process. The traction engine, which towed the threshing machine, chaff-cutter and a straw elevator, was limited to a speed of 2-3 mph. Manoeuvring this train of vehicles through narrow country lanes and into small stackyards or field corners required patience and skill. Understandably, the range of the typical threshing contractor was not more than 6 to 7 miles from his home base.

Most contractors sent out two men with each threshing set, one to look after the engine and one to feed the threshing drum. An additional contractor’s man was needed when the chaff cutter was operated. A further 8 or more men were brought in and paid for by the farmer for tasks such as handling the sheaves, cutting the bands, moving sacks of grain, stacking straw and fetching water. A small farmer was very likely to turn to neighbouring farms for extra workforce which could be shared on a reciprocal basis. The contractor’s own employees would usually find casual work in the summer months when the threshing machine was in little demand.

Many contractors had 3 or 4 threshing sets, though probably only one chaff cutter and only one machine designed for, or adaptable to, hulling clover and threshing other crops. A traction engine with 7 or 8 HP rating was best suited to this work. In the early twentieth century a day’s threshing – 8 or 9 hours – would be sufficient for a 10 or 12 acre field of wheat, yielding about 12 tons of grain. The use of threshing contractors declined in the 1920s as tractors with power-take-off were introduced and stationary oil engines were an alternative source of power on the farm. Combine harvesters, which both cut and threshed cereal crops, were not in common use until the 1950s.

Description of the document

William and Henry Reed, blacksmiths of Thorpe on the Hill near Lincoln, also worked as threshing contractors from the early 1880s until about 1920. A day book or payments diary recording the work they undertook from 1909 to early 1916 is the source of the data for these spreadsheets.

Figure 2 (Reed brothers with portable engine)

Each entry in the book records the date, name of customer, type of activity (threshing, chaff cutting, etc), duration of activity, identity of employees and the charge made for the work. The handwriting, in pencil, is not always very legible and there are many uncertainties and omissions. Where it is possible to be confident about the identity of unclear or missing information, this has been included in the data transferred to the spreadsheet.

As well as recording the day to day activities of the business in a systematic manner, the contractor also made notes in the day book – or on slips of paper inserted in it – of other related matters. These include details of a loan of his clover huller on 20 occasions in 1918 and 1919, a record of payments made to his staff over a two-week period in February 1914, and an occasion when he helped pull another contractor’s traction engine from a roadside ditch.

Downloadable Files

NOTE: PROBLEMS WITH GOOGLE CHROME

If you are using Chrome as your browser, you may find that it refuses to upload spreadsheets out of concern that there are macros in it. (There aren’t). You may find it easiest to use another browser.

Alternatively, if you click on a link and nothing happens, do a right-click and Copy the address into a new tab of the browser. Press Return, and if you get a warning message click the Keep button on it. The spreadsheet should then load in the normal way.

SPREADSHEET 1: Contractor’s Day Book, 1911 (Excel Format)

Threshing Contractor – Spreadsheet 1 – 23 Nov

The first sheet covers the full entries made by the contractor for the year 1911. This year has been chosen for two reasons: firstly, it was the year of a national census, which provides names and locations of all the individuals likely to be included in the contractor’s records. Secondly, it coincides closely with the Valuation Office Survey set up by the Inland Revenue in 1910, a survey which lists the owners and occupiers of every of piece of land and property in England along with acreages and valuations.

Format used in Spreadsheet 1

Column A

Date

Column B

Name of customer

Columns C, D (headed E and N):

Easting and northing (grid reference) of customer’s location. Four-figure grid references have been given, approximating to the centre of a village, because it has not been possible to identify a more precise location of most farmsteads.

Column E (headed X)

In a few instances it is not known in which village a customer’s farm was located. These have been marked ‘X’.

Column F (Days)

Number of days worked. The common practice among contractors was to measure time in days or fractions of days rather than hours. It was also the practice to account separately for each day. So, for example, the visits to J Taylor’s farm (rows 10, 11, 13 14)) appear in four lines in the book – two half days and two full days – rather than as a single entry for 3 days-worth of work.

Column G (Q)

When the time spent on a visit was significantly less than the usual full or half day, entries in the book are marked ‘small’ or ‘long’ and the charge modified accordingly. Small and long days are marked ‘S’ and ‘L’ respectively in this column.

Columns H to M (Thr, Cur, Hul, Saw, Bea, Mus)

The type of activity: threshing corn, chaff cutting, hulling clover, sawing wood, threshing beans, threshing mustard. Threshing and cutting frequently took place concurrently on a single visit.

Columns N to S (R, P, C, G, H, Other)

Initials of the contractor’s employees, two of which share the letter ‘H’. Under column S (Other) a surname, in full or abbreviated, is occasionally given and has been, as far as possible, exactly transcribed from the document.

Column T (Chge)

Charge for activity (shillings). (The day book actually records charges in £ s d.) The contractor’s practice was to strike out the figure when payment had been made.

SPREADSHEET 2: Summary for 1909-15 (Excel Format)

Threshing Contractor – Spreadsheet 2 – 23 Nov

The second sheet gives monthly totals of days spent in threshing and other activities over the seven-year period covered by the book (January 1909 to January 1916). It is subdivided into threshing years (August to July) rather than calendar years. Also included are the charges made by the contractor during this period.

Format used in Spreadsheet 2

Columns A, B

Year and month

Columns C – G (Thr, Cut, Hul, Saw, Be/Pe)

Time spent (days) threshing grain, chaff cutting, hulling clover, sawing timber and threshing beans, peas or mustard

Column H (TOTAL):

Total time spent. Note that on many occasions threshing and cutting occurred simultaneously.

Column I (Chge)

Total of charges made by the contractor during the month (shillings)

Analysis and Discussion

It is apparent that the contractor operated three threshing sets. During the peak of the threshing ‘season’ in the early autumn there are three entries for almost every working day but never more than three (Spreadsheet 1). The pattern of visits also indicates that the contractor had a single machine for hulling clover and grasses. He also operated one chaff cutter and occasionally let a traction engine out as a power source for sawing timber.

Threshing Grain

The contractor’s principal work was threshing cereal grain, an activity which took place mainly from early autumn through to the end of March. Occasionally, the contractor was called out for a day’s threshing in the late spring and summer; this was probably for threshing oats for animal feed for immediate use rather than yielding grain for selling to the market.

There was an intense period of about ten weeks in the autumn each year when the three threshing machines were in operation almost every day from Monday through to Saturday. On average the contractor’s threshing machines were active for about 85% of the time during this critical ten-week period. Some loss of time could probably be attributed to factors such as machinery break-down, seriously adverse weather conditions, travel between sites (see below), and the requirements of the smallest farmers which were impossible to accommodate in convenient full or half-day sessions.

The timing of the peak threshing activity varied from year to year according to the weather and the consequent completion date of harvesting. Most commonly, threshing of the newly harvested crop began in early September. However, there was one exceptional year covered by the day book. In 1911 all three threshing sets were fully deployed from the middle of August, almost three weeks earlier than usual. That summer was said to have been the hottest and driest in the memory of man and as a consequence the harvest was extremely early. Threshing also began before September in 1914 – another hot, dry year, especially in August – but otherwise, in all the other years covered by the day book, August was the quietest month for the contractor and threshing did not commence until the first few days of September.

The table below gives dates which indicate the timing and profile of the threshing programme each year.

|

Threshing Year |

Start date |

‘Full Speed’ |

Halfway Point |

|

1909/1910 |

1 September |

7 September |

17 November |

|

1910/1911 |

2 September |

8 September |

7 November |

|

1911/1912 |

8 August |

17 August |

17 October |

|

1912/1913 |

7 September |

11 September |

20 November |

|

1913/1914 |

30 August |

10 September |

6 November |

|

1914/1915 |

15 August |

21 August |

5 November |

|

1915/1916 |

1 September |

8 September |

– |

Threshing Year – August of one year through to July of the next

Start Date – The day on which threshing the new crop began

‘Full Speed’ – The day from which the contractor began using all three threshing machines each day

Halfway Point – The day on which the contractor was halfway through the total days spent on threshing in that threshing year

The sequence of dates in each year follows a consistent pattern, albeit shifted earlier or later according to the weather conditions and the completion date of harvest. There is one notable anomaly: in 1914/1915 the halfway point was reached about two weeks later than might be expected. This was because the number of cereal threshing days taken on by the contractor in that year increased by about 30% compared to the previous five years. 1914/15 was the first full year of the First World War and a number of abnormal factors may have come into play.

In the first place, there were widespread labour difficulties as many agricultural workers volunteered for war service and could not be replaced readily; the reduction in the total agricultural workforce in this period is estimated to be about 10%. The war also took large numbers of horses from farm work for a variety of haulage tasks on the western front; of the estimated one million horses deployed in agricultural work in Britain about 70,000 were impressed in the first two years of the war.

Although the national ‘ploughing-up’ campaign, which exhorted farmers to convert grassland to arable land for growing cereals and potatoes, was not introduced until 1917, from the early days of the war there was widespread recognition of the need for a substantial increase in home produced food. Almost 20% more wheat was grown nationally in 1915 than in the immediate pre-war years , though the farmer may have had his own profit in mind as much as the nourishment of the nation when he committed a greater acreage to the crop. The shortage of the cereal in wartime conditions would lead to a higher market price, he believed, and the steep rise in wheat price from 34s 11d per quarter in 1914 to 52s 10d in 1915 subsequently proved him correct.

Without detailed knowledge of local circumstances it is impossible to judge the effect that these or any other wartime factors had on the activities of this threshing contractor. It could simply be that he was more active than usual because other local contractors reduced their operations or ceased trading altogether. The fact remains that the Reeds took on additional threshing work in the first full year of the war, and regrettably the termination of the day book in early 1916 makes it impossible to know whether the increased level of business was sustained for the remainder of the war.

Other Activities

The contractor’s chaff cutter was used for about 50 days each year. Apart from a period in summer when they grazed outdoors, horses were fed in stables where chaff was an essential ingredient of the daily diet. Chaff cutting therefore took place mainly from autumn through to spring, though the frequency of demand from individual farmers depended to a large extent on their storage arrangements for this bulky material and, in the case of small farmers, whether they chose to cut chaff by a hand-operated machine. The day book makes clear that the contractor’s chaff cutter was sometimes operated alone by a traction engine but more frequently was powered indirectly by a drive pulley on the side of the threshing drum when the contractor was already on site threshing grain.

Hulling clover and grasses was mainly confined to winter and early spring, prior to the sowing season. Clover was usually undersown with main crop barley or wheat. The time spent in this activity by the Reeds varied widely from year to year; it was more than 85 days in the winter of 1913/14 but less than two days in 1912/13. The seasons 1914/15 and 1908/09 were also busy, while 1909/10 was very quiet. It is unlikely that these variations reflect significant changes in the general pattern of crop growing in this part of Lincolnshire but rather indicate the effect on clover yields of differing weather conditions from year to year. Clover is particularly vulnerable to cold weather in the spring and wet conditions at harvest. Seed was usually taken from a second growth of the crop after the first cut was used for forage so, in an indifferent year, this would have led to little being harvested and threshed in the winter.

A handful of days were spent threshing peas and beans, crops grown on a small scale for feeding livestock on the farm. A threshing machine could be modified readily to handle this work. On one occasion the contractor records a day threshing mustard; this crop was probably grown under contract. Each year, for a period of several days during July and August, the contractor supplied one of his traction engines for sawing timber on the Doddington Hall estate where there was a fixed or portable saw bench. A belt drive from the contractor’s traction engine provided the necessary power.

On several occasions the contractor hired out a portable steam engine at a rate of 12 shillings per day, with no man in attendance. A machine of this description had been used by the Reeds as the source of power before the introduction of the self-moving traction engines which operated in the period covered by the day book (see Figure 2). The farm which hired the engine probably had a fixed threshing machine on site. Examples of this business are seen in several years, though not in 1911. The related income has not been included in the figures in Sheet 2.

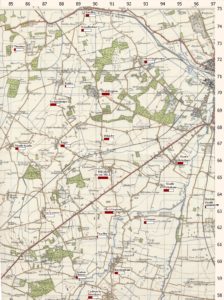

Location of Customers

The employees’ initials recorded as part of the entries in the book strongly suggest that each threshing set was associated with a particular pair of men, especially in the early autumn when all three sets were being used. This makes it possible to track the movement of each threshing machine from day to day, though the uncertain identity of some customers and their allocation to villages rather than particular farm sites make this an imprecise exercise. Nevertheless, as might be expected, it can be seen that almost all consecutive moves of a particular threshing set were between sites within the same village or between neighbouring villages.

One clear exception to this rational scheme of movement occurred in September 1911. On Monday 11 September and Tuesday 12 September a threshing set with employees C and G worked at Harrison’s farm in Swinethorpe (Sheet 1, rows 244 and 247, NGR SK 8769). On Thursday, Friday and Saturday of the same week the same set was at Priestley’s farm in Carlton le Moorland (rows 253, 253, 259, NGR 9158), about eight miles distant. On the following Monday, 18 September, the set had moved to Vickers’ farm in Doddington (row 263, NGR 9070), another journey of eight miles. No work is recorded for this threshing machine on Wednesday 13 September, the day between the first two visits; presumably this day was taken up in moving the threshing set between Swinethorpe and Carlton. The second long journey, from Carlton to Doddington, estimated to take approximately four hours, probably took place on Sunday 17th. There may be other anomalies of this sort.

Contemporary trade directories indicate that the nearest alternative threshing contractors at the time of the Reeds’ day book were in Newton on Trent (about 7 miles from Thorpe in a north-westerly direction), Burton by Lincoln (6 miles, north), Lincoln (5 miles, north-east), North Hykeham (3 miles, north-east), Branston (7 miles, east), Navenby (7 miles, south-east, Norton Disney (4 miles, south) and Swinderby (3 miles, south-west). There may also have been contractors in villages such as Collingham, Harby and South Scarle (6, 4 and 4 miles respectively from Thorpe, to the west) beyond the county boundary in Nottinghamshire but these have not been identified.

Many of the villages visited by other contractors would have been those where some of Reeds’ customers were located. If one compares the farmers identified in the Reed day book in 1911 with those listed in Kelly’s Directory of Lincolnshire 1913, it is possible to get an estimate of the proportion of farmers in a village that were served by the Reeds. Not surprisingly, it appears that Reeds had a complete monopoly of threshing in Thorpe, their home village; every name in the directory also appears in the Reeds’ day book. Similar comparisons between the names in the day book and the 1913 directory listings indicate that the Reeds were also employed by all the farmers in Haddington (2 miles away); by 50% or more of the farmers in Doddington (2 miles), Swinethorpe (3 miles) and North Hykeham (3 miles); and between 25 and 40% of the farmers in Whisby (1 mile), Eagle (2 miles), South Hykeham (2 miles), North Scarle (4 miles), Bassingham (4 miles), Skellingthorpe (4 miles) Saxilby (5 miles) and Carlton le Moorland (5 miles). In a few villages – some of which, but not all, were at greater distances from Thorpe – they had only one or two customers: Thurlby (3 miles), Swinderby (3 miles), Aubourn (3 miles), Norton Disney (4 miles), Harby (4 miles), Broadholme (5 miles), Thorney (6 miles), Navenby (7 miles) and Nocton Heath (8 miles). The majority of farmers in this last group of villages would have been using threshing contractors other than the Reeds.

Figure 6 (Threshing ‘train’ on the road)

Employees

In order to run his full complement of machinery the contractor needed a minimum of seven men, two for each threshing set and one for the chaff cutter. (Hulling clover and threshing minor crops only took place when one of the threshing sets was inactive.) However, in the course of 1911 as many as fourteen different initials or names are recorded in the day book. The regular men are identified as R, P, C, G, H and H; their initials appear fairly consistently throughout the year. Other initials and names (Spreadsheet 1, column S) sometimes indicate the operator of the chaff cutter; on other occasions they probably represent substitutes for the regular men.

One of the men regularly indicated by the letter ‘H’ may be Henry Reed (born 1867), the younger of the two brothers running the business; the identity of the other men is unknown. Unfortunately the Census of 1911, which gives occupational details of all the working men in Thorpe, was taken in early April when little threshing was taking place and the contractor’s men were probably engaged in other work. Apart from the two Reed brothers, only one individual in Thorpe – Henry Taylor, aged 22, described in the Census as traction engine driver for a threshing machine – can be linked to the contractor’s threshing business. The name of Taylor, or an abbreviation of it, occasionally appears in the details for 1911 in the day book, but it is more likely that Henry Taylor is indicated by one of the two frequently occurring Hs and that ‘Tay’ refers to another Taylor (there were several in the village, including Henry’s father, described as a farm labourer in the Census return).

Financial

A charge of 28 shillings was made for a day’s threshing throughout the period covered by the day book until August 1915 when it was raised to 31 shillings. Occasional variations are seen in these figures when the period of work was assessed as being longer or shorter than normal or when other unexplained factors came into play. The daily rate for chaff cutting was 14 shillings, hulling 40 to 45 shillings and the hire of a threshing machine for sawing (with one contractor’s man in attendance) 16 shillings.

The daily charge for threshing made by the Reeds appears to be well below the average. In the early 1920s the standard rate in Cheshire was £5.12s per day and in Gloucestershire it was £2.15s. Another source quotes a charge of £3 per day in Kesteven in 1923. However, direct comparisons are difficult to make without clear knowledge of what machinery and manpower were included in the charges.

The wages received by three of the contractors’ employees for a six-day week in February 1914 were 18s 3d; at the same time Henry Reed, co-owner of the business, received £1.0s.3d. The men’s wages, which are unlikely to have changed significantly over the period covered by the day book, were perhaps 10% higher than those paid to the highest grade of farm worker. They appear to be close to typical figures for this occupation in the period.

The contractor is known to have purchased two second-hand traction engines sometime between 1905 and 1910. (They were a Ransomes Sims & Jefferies, 7HP, single cylinder, No. 17197, and an Allchin, 8HP, single cylinder, No. 493; both were sold in 1917.) It is not known what the purchase prices were or what financial arrangements were made for payment.

Acknowledgements

Mrs Mary Hardy, grand-daughter of William Reed, one of the threshing contractors, passed the day book to the late Ruth Tinley for deposit at Lincolnshire Archives in 2013. Ruth generously allowed access to the book before the deposit. Robert Hardy, great-grandson of William Reed, has given his support to the project and Paul Smith has given permission to publish Figure 2. Helpful comment and advice have been given by Chris Page and Alan Stennett. Rob Wheeler, as series editor, has guided this material through to publication.