The Witham Toll Accounts

R C Wheeler

Background

As late as the 1730s, most of Lincoln’s trade was through Boston, but the River Witham that linked the two was already starting to deteriorate. After failing to obtain an Act to improve the river, Lincoln Corporation had turned its attention to the Fossdyke Navigation which linked the city to the Trent. In 1741 it granted a 999-year lease of the Fossdyke to Richard Ellison of Thorne, subject to his deepening it to maintain a depth of water of 3ft 6in at all seasons. Ellison’s son (another Richard) completed the work in 1745 and thereafter most of Lincoln’s trade went northwards to the Trent and Humber. The Witham continued to silt up and by 1753 the section below Chapel Hill had silted up almost entirely, the water finding a new course across to what is now known as the North Forty Foot Drain, by which it reached Boston. The consequent loss of grazing in the fens was so bad that eventually agreement was reached and in 1762 the Witham Act[1] was passed.

This set up Drainage Commissioners empowered to improve the River Witham and to levy a drainage rate on lands benefiting, along with Navigation Commissioners, empowered to build locks and remove shoals and to levy tolls on traffic using the river. Having two sets of commissioners was intended to reconcile the conflicting interests of landowners and traders, but in practice there was a certain commonality of membership and close cooperation. Both sets of commissioners had the power to mortgage their prospective receipts in order to generate a capital sum for the initial works. One must not be misled by the apparent symmetry: the Drainage Commissioners raised £53,650 on their future revenues and by 1765 had dug a new channel from Boston to Chapel Hill. The Navigation Commissioners could raise a mere £6800; it was 1771 before locks had been built all the way up to Lincoln.

The Act stipulated a maximum toll of 1s6d per ton. Until the new channel had been dug, the Drainage Commissioners were to maintain the North Forty Foot and during this period the Navigation Commissioners were empowered to collect a toll of up to 6d per ton on it, with traffic within Holland Fen being exempt. The logic for this is that traffic between Lincoln and Boston must have been using the North Forty Foot; perhaps the naturally created link south of Chapel Hill was navigable, or possibly transshipment took place at Kyme Eau. The exemption reminds us of the widespread use of drainage channels by boats. There was rarely specific provision for them, so transshipment of goods must have been common, but boats still offered cheaper transport than carts. One of the great unknowns for this period is how goods reached Sleaford or Horncastle. There are a couple of references to goods from Lincoln to Horncastle transferring to road at Tattershall Ferry[2], but it seems likely that some use was also made of the River Bain and the Slea / Kyme Eau even though these were not turned into proper navigations until the end of the century.

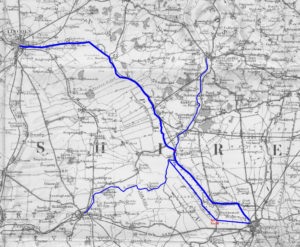

The principal waterways mentioned, with the intermediate toll stations, drawn on the OS Quarter-inch of 1914 (Click to enlarge image).

The Witham Navigation Commissioners set up toll stations at Lincoln and at Toft Tunnel on the North Forty Foot. The latter seems an obscure location, but it may have been chosen in preference to Boston from a concern that tolls at a station closer to Boston might have been evaded by transferring goods to carts (something which probably needed to be done anyway) upstream of the toll station. By February 1765, the new cut to Chapel Hill was functional so far as drainage was concerned and the power to collect tolls on the Forty Foot lapsed. Accordingly the station was moved to Dogdyke, a little above Chapel Hill. Again its position may seem a little curious. The fear was now, perhaps, that traffic might continue to use the Forty Foot in order to avoid paying tolls at the Boston end; placing the station above Kyme Eau ensured that through traffic using this route paid tolls. The Dogdyke station was placed at the junction with the ‘Twelve Foot’. In addition to a chain across the Witham to ensure that boats stopped and paid, a chain was placed across the Twelve Foot, which implies that some traffic was expected to use this channel too. No other reference to the Twelve Foot has been found but it seems likely that this was the navigable channel of the River Bain. Later in the century Gibson’s Canal was cut from the Witham to Tattershall, and it might be presumed that navigation along the Bain from Dogdyke then ceased. But this is necessarily speculative, and the toll accounts tell us no more about the Twelve Foot.

The rate charged at Dogdyke was 6d per ton. It is assumed that this rate had been charged also at Toft Tunnel (being the maximum allowed under the Act). The rate at Lincoln is not stated anywhere, but 6d per ton seems likely. A couple of vouchers relate to constructing a Boston toll station, something that only came about a year later[3]. Perhaps there was an aborted plan for three stations, each charging 6d per ton at the two ends of the navigation and at Dogdyke, about mid-way. This would have had the merit of fairness as between Lincoln and Boston, and would have set total tolls at the maximum permissible. Certainly, a rate of 6d per ton at Lincoln makes the figures for tonnage there consistent with the other stations; a rate of 1s per ton at Lincoln would lead to tonnage figures that are incompatible with the others. Accordingly, in what follows it is assumed that toll stations at all three locations charged 6d per ton.

Collectors received a salary of £20 pa. The Dogdyke toll station consisted of a wooden hut on the river bank, with a brick chimney. It would appear that the collector was expected to be in attendance there 365 days per year throughout daylight hours. The salary amounts to slightly over 1s per day, less than a labourer’s wage, notwithstanding the responsibilities. The money was collected only every four months, by which time accumulated tolls might amount to £50. It would appear to be a job for an elderly farmer or craftsman, no longer fit for strenuous work, and living in a multi-generation household – otherwise those accumulated tolls might offer temptation to robbers. Or perhaps we should envisage the station being manned much of the time by a grandchild, who runs to fetch the collector when a boat is seen approaching. We do know that there were only a couple of boats paying toll each day, so the collector actually had very little to do.

The Treasurer to the Navigation Commissioners was Richard Fydell, a substantial wine merchant of Boston. He presented his accounts to a General Meeting each July. Compared to the Fossdyke accounts of fifty years earlier his accounts are amateurish and exceedingly casual, little more than cash receipts and expenditure. Most of the expenditure consisted of payments ‘on account’ to Langley Edwards, the engineer; not only were payments related to the construction work handled in this way, but also payments relating to the routine running of the navigation. In 1763, the commissioners instructed Edwards to account for these sums once the total had reached £300; in 1767 the limit was raised to £1000; it is not clear that Edwards ever did present accounts.

The Documents

NOTE: PROBLEMS WITH GOOGLE CHROME

If you are using Chrome as your browser, you may find that it refuses to upload spreadsheets out of concern that there are macros in it. (There aren’t). You may find it easiest to use another browser.

Alternatively, if you click on a link and nothing happens, do a right-click and Copy the address into a new tab of the browser. Press Return, and if you get a warning message click the Keep button on it. The spreadsheet should then load in the normal way.

Of the little that survives from the early years of the navigation commissioners most is unfit for production. Fortunately, a copy was made of the minutes, probably in the mid-19th century for the Great Northern Railway, and this survives at the National Archives. The documents presented here have survived as strays, mixed up with the Drainage Commissioners’ records.

Two of the Treasurer’s reports to annual meetings have long been known about[4]. Both give monthly receipts by toll station. The 1765 one allows direct conversion to tonnage figures, presented here. The 1775 one suffers from a change in the toll structure made in 1770 which means one can no longer convert a monetary amount to a tonnage. Figures are converted to decimal shillings, for ease of analysis. This sheet has three lines for totals. ‘Total’ gives the value in the document; Actual total gives the sum of the entries – there is a discrepancy for Lincoln; Gross total adds in the collectors’ presumed salaries, which have been deducted from the nett figures returned in the document.

More recently, it has been discovered that a bundle of vouchers[5] relates in part to the navigation accounts of 1765 and includes a set of monthly returns from Dodyke listing each load and the toll it paid.

To enlarge on the Treasurer’s 1765 account, the spreadsheet gives a 12-month run of figures for Lincoln, 12 months for Toft Tunnel and 5 months for Dogdyke. This is because 12 months earlier, in July 1764, Fydell had failed to collect the last 4 months’ receipts from Toft, so these had to be deferred to the 1765 accounts. For February 1765 there are monthly figures from both Toft and Dogdyke because the move of the toll station took place early that month. Between about 4 Feb and 9 Feb, tolls were being collected at neither place, so the February tonnage figures are necessarily defective.

The monthly returns by Robert Short, the Dogdyke collector, are presented here combined as a single spreadsheet. The originals consist of five monthly lists, fair copies drawn up possibly by Langley Edwards’ clerks[6]. All lists give date, name, quantity in tons, and amount paid. The last of these is always calculated at 6d per ton so has been omitted from the spreadsheet. Note that 200 years have added to the dates to accommodate the limitations of Excel. Note also that to allow efficient sorting, the first spelling encountered for a name is maintained for all subsequent occurrences, even when the original spellings vary.

The June list, very usefully, gives the commodity carried. There are annotations of this nature on one or two entries from other months. The March and April lists are annotated with figures headed ‘White’. Luke White was the collector at Lincoln and these annotations appear to be a comparison made by Edwards or his clerks between a boat’s tonnage at Lincoln and the same boat’s tonnage at Dogdyke, as a check on Short’s honesty.

There was always a temptation for a collector to come to an arrangement with a boatman whereby the latter escaped toll altogether or paid less than he should have, in return for some form of gratuity to the collector. To guard against the first option (and that of charging the toll and pocketing the receipts) the collectors were required to issue printed receipts. If a boat was checked at Boston and lacked a Dogdyke receipt or had a receipt for which the sum had not been entered in the collector’s list, then the collector would be in serious trouble. But most commodities travelled loose and without manifests; one can easily imagine arguments between boatman and collector about just what quantity there was in the boat; and it was all too easy for the collector to accept the boatman’s claim uncritically, especially if encouraged by a douceur. And indeed the tonnages in Short’s lists do tend to be a little less than those in White’s. Some of the difference may be accounted for by sales of coal en route; and Short was new to the job. At any rate the checks stop after April: presumably it was decided that Short was doing his best.

The last four columns give monthly subtotals. The first is tonnage, calculated within the spreadsheet. The second, headed In Shillings, is that given in the document converted to decimal shillings. The difference between these two figures (in shillings) is given. Finally, the tonnage is totalled for the Lincoln figures – ie the annotated figures headed ‘White’.

Analysis

Monthly Figures

It is best to start with the report to the 1765 Annual Meeting and to consider separately the periods up to January 1765 and March-June 1765 when the toll station had moved.

For Toft Tunnel, we have an 11-month run of figures showing a fairly stable level of trade. That January 1765 is the lowest month may possibly indicate some shipments from Lincoln being delayed until the new river channel was open. In contrast the Lincoln figures from July to January show much more variation. The slump in November is particularly surprising: it is a little early for a freeze-up and there are no known engineering works that might have caused a stoppage.

Note that the Lincoln figures are typically four times as high as Toft’s: most of the traffic that leaves Lincoln does not travel as far as Toft. Comparison of the two sets shows that the Toft figures seem to move in sympathy with the Lincoln ones but the movement is relatively small. If we fit a linear equation, we obtain

Toft = 64 + 0.137*Lincoln.

This would correspond to 64 tons/month of trade on the Forty Foot which has nothing to do with the upper part of the Witham (trade to Sleaford, perhaps) combined with 13.7% of the Lincoln traffic continuing to Boston. It is a pattern that reflects the difficulties of getting between the two waterways at Chapel Hill and may well go back to before 1762. If 13.7% of Lincoln trade continues to Toft, the other 84.3% is for destinations en route. This may be for Horncastle (by road from Tattershall Ferry or by proceeding some way up the Bain), for Sleaford via Kyme Eau and as much of the Slea as was passable, or for smaller places like Bardney. Thus these intermediate destinations in total averaged 489 tons per month in this period.

For the period from March to June, we see a doubling of trade at Dogdyke, while Lincoln traffic grows by a mere 30%. The pattern in this period is not stable. First, there appears to be a genuine growth in traffic on the new channel. Secondly (and the evidence for this comes later) some of the trade in May and June consists of special shipments in connection with construction works at Boston. With so short a run of monthly figures it is difficult to separate these two effects.

Commodities in June

Turning now to the Dogdyke monthly returns and specifically the commodities carried in June, totals are presented below. Where two commodities are lumped together in the descriptions, it has been assumed that about 60% of the total can be attributed to the first-named. Such instances are relatively few, so this assumption will have little effect on the results.

Most of the descriptions are straightforward. Under Wood Products, rails will be for fences; stulps are posts, either for fences or for gates, timber is more generic, and wood may well refer to small stuff intended for firing ovens and suchlike. Stones appears to be a reference to the carriage of limestone from Lincoln to Boston, to be burned there to produce lime for the major works in progress. Goods means merchandise: anything not carried loose.

|

Category |

Commodity |

tons |

category total |

|

bricks |

13 |

||

|

lime |

12 |

||

|

pavings |

14 |

||

|

reed |

14 |

||

|

Building materials |

53 |

||

|

rails |

20 |

||

|

stulps |

4 |

||

|

timber |

12 |

||

|

wood |

31 |

||

|

Wood products |

67 |

||

|

beans |

7 |

||

|

corn |

8 |

||

|

flour |

2 |

||

|

Foodstuffs |

17 |

||

|

coal |

282 |

||

|

stones |

196 |

||

|

goods |

60 |

||

|

GRAND TOTAL |

675 |

Coal, unsurprisingly, was the largest category. Some of it will be sea-coal, brought by ship to Boston from the North-East; some will be pit-coal, brought from Yorkshire via the Fossdyke. In order to determine the relative importance of each, the March and April returns were used to categorise boatmen as ‘Lincoln men’ – those for whom there was usually a figure for tonnage at Lincoln – and ‘Boston men’ – those for whom there was not usually such a tonnage figure. It seemed reasonable to suppose that coal carried by ‘Lincoln men’ was pit-coal, whilst that carried by ‘Boston men’ was sea-coal. On that basis, there were 123 tons of pit-coal, 52 tons of sea-coal, and 107 tons that could not be categorised – usually because the boatmen did not appear in March or April. The idea that coal was coming to Dogdyke from both directions and even crossing is quite plausible, because sea-coal was preferred for domestic use (and attracted a higher price) whereas pit-coal was preferred for some other processes like lime-making. If we split the unknown 107 tons in the same proportion as that which we know about, we can estimate the June total as comprising 84 tons sea-coal and 198 tons of pit-coal. We can be fairly confident that at this date sea-coal was no longer sold in Lincoln, so these figures seem to show pit-coal and sea-coal in serious competition for the domestic market in Horncastle and Sleaford, while some pit-coal is reaching Boston, perhaps only for industrial uses.

‘Stones’ as an exceptional item

The presumed limestone deserves special attention. It is carried by just 6 boat operators, each making as many as three trips in the month. The consignments are much larger than average: the largest (26 tons) must represent multiple hulls. Several of these operators do not appear before May; those that do appear show a more low-key pattern in their earlier activity. All in all, the traffic in ‘stones’ is reminiscent of the traffic in building stone observed from the Fossdyke accounts: a burst of activity which attracts different operators and shows patterns of movement not usually seen. All this suggests it represents exceptional activity which probably started in May.

The Grand Sluice itself might seem a possible destination for this stone: we do know that lime was being burnt on-site for mortar. However, in 1765 only the navigation lock was under construction; the rest of the structure with its three great drainage channels was complete. If limestone was being brought from Lincoln for the navigation lock, there surely ought to have been larger consignments the previous summer for the rest of the structure; and yet the total quantity at Toft Tunnel never rises as high as 198 tons. As it happens, reconstruction of the Black Sluice at Boston was under way in 1765 – the responsibility of a different drainage trust – so it may be this that occasioned the movement of so much limestone.

At any rate, the limestone ought to be treated as an exceptional item, which should be removed if we wish to examine the normal pattern of trade. This has been done in the table below, deducting this 198 tons from the June figures, and half that amount from the May figures.

|

Month (1765) |

Dogdyke |

Lincoln |

|

Feb |

85 |

370.5 |

|

March |

328.5 |

584.5 |

|

April |

337.5 |

617.2 |

|

May |

439 |

685 |

|

June |

491 |

574 |

Dogdyke figures are still rising in June but the rate of increase has slowed; Lincoln figures have stabilised at a little over 600 tons. This is necessarily a somewhat tentative estimate, because of uncertainty over just when the limestone traffic started, but we can be confident it was not present in March and we have exact figures for June, so the general picture is fairly reliable.

What went where

For March and April we know how much of the Dogdyke traffic had come from or was bound for Lincoln. Those totals appear in the centre column of the table below.

|

Month |

Dogdyke Total |

Dogdyke only |

Dogdyke & Lin |

Lincoln only |

Lincoln Total |

|

March |

328.5 |

69.5 |

258 |

326.5 |

584.5 |

|

April |

337.5 |

106.5 |

232 |

385.2 |

617.2 |

It follows that the rest of the traffic recorded at Lincoln was for destinations short of Dogdyke (described here as ‘Lincoln only’. Likewise, the rest of the traffic at Dogdyke (‘Dogdyke only’) was bound for destinations other than Lincoln. Downstream from Dogdyke, the new cut passed through what had formerly been empty fen. With the possible exception of reed, which may have originated there, we can be confident that traffic is bound for, or coming from, Boston. In the other direction it may be for Horncastle via the 12-foot channel or for destinations like Bardney. The traffic in the ‘Dogdyke & Lincoln’ column may be for Horncastle via the 12-foot, or for Sleaford via Kyme Eau, or for Boston.

The equivalent of the ‘Lincoln only’ column in the period before the new cut opened was averaging 489 tons/month but this included Lincoln-Sleaford traffic, now caught by the new toll station.

The ‘Dogdyke only’ column starts at 69.5 tons, which bears a gratifying similarity to the ‘Toft only’ figure estimated from regression analysis. What is important is that both are fairly small. ‘Dogdyke only’ does seem to be growing. In the table that follows, extrapolated figures for this column have been entered in italics. The ‘Dogdyke & Lincoln’ column follows by subtraction, and the ‘Lincoln only’ column by subtraction from the Lincoln total. These figures are given in blue to show that they are deductions from this first extrapolation. The June figure was actually derived from the analysis for coal reported earlier, assigning sea-coal to the ‘Dogdyke only’ column, pit-coal to ‘Dogdyke & Lincoln’, and apportioning other commodities in the same proportions as coal.

|

Month |

Dogdyke Total |

Dogdyke only |

Dogdyke & Lin |

Lincoln only |

Lincoln Total |

|

May |

439 |

110 |

329 |

356 |

685 |

|

June |

491 |

146 |

345 |

229 |

574 |

There a a noticeable fall in the ‘Lincoln only’ column. This might be explained as Sleaford and Horncastle tending to look more towards Boston, especially for their supply of coal. Figures for the period after June would be really helpful but sadly do not exist.

Making sense of 1775

In 1770, the Navigation Commissioners decided on a new toll structure[7]. Henceforth tolls would be collected, not only at Lincoln and Boston (to which the Dogdyke station had been moved in 1766) but also at the intermediate locks (Barlings and Kirkstead). Loads would pay 1s per ton at the first such point, with a further 6d per ton on subsequent arrival at Lincoln or Boston. It was a curious structure, perhaps intended to extract the highest tolls the Act permitted while seeming to maintain a measure of fairness.

Total receipts had risen from a little over £250 in 1764-5 to just under £300. The most important question to address is whether this represents a continuing increase in trade or is simply a consequence of the increased rates. But first we must cast a critical eye over the document. Whereas in 1765 the collectors’ salaries appear as ‘contras’, in 1775 the monthly figures are described as receipts ‘beyond salary’. The Kirkstead and Barlings figures in contrast are gross, because salaries ‘to Michaelmas’ (ie half-year salaries) to those two individuals appear as contras. That tells us that the lock-keepers, like the 1765 collectors, were paid £20 per year, and this sum has been added back in to the Lincoln and Boston figures. It is of course possible that the collectors’ jobs at Boston and Lincoln had attracted other duties which brought an increase in salary. However, even in 1765 the collectors had been in the practice of deducting their monthly salary from the sum they handed over to the treasurer, the deduction in question being one-twelfth of £20, viz 33s4d.; if we add 33s4d to each monthly figure in 1775, the result is always a multiple of 1½d, which is a 6d toll on ¼ ton. Such precise estimation of weight may seem surprising, but grain was moved in quarters and (on the Fossdyke, at least) wheat was reckoned at 4 quarters to the ton, so the odd three-halfpence may be explained as a consequence of cargoes of grain. This provides a measure of confirmation that collectors’ salaries had not changed since 1765.

It is no longer possible to deduce a simple total for the quantity of goods shipped. A question we can pose is whether the pattern of trade seen in June 1765, had it continued, would have led to toll receipts comparable to those recorded in 1775. Even that is not easy, because the categories extracted from the 1765 accounts – Dogdyke only, Dogdyke & Lincoln, Lincoln only – do not map across tidily to the new structure. However, these three categories represent trips that would attract a toll of at least 1s/ton (apart from a few highly improbable trips like Sleaford to Horncastle, which are more than counter-balanced by Sleaford-Boston, which paid nothing at all under the 1765 arrangements). Thus the 720 tons of movements we believe occurred in June 1765 would have paid at least £36 in 1775, which equates to £432 in a full year. Actual gross tolls in 1775 were slightly under £300.

Perhaps we have under-estimated the exceptional traffic in June: it is plausible that some of that month’s coal, for example, was being shipped to Boston to burn the limestone. But if we look at the April traffic and we add together the three categories, we obtain 723.7 tons, slightly more than our June estimate, so the annualised tolls would be even greater. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that there was a real decline in traffic. The most likely explanation is that the new tolls were high enough to cause traffic to move by alternative routes. The use of drainage channels rather than the Witham as a means of reaching Sleaford and Horncastle is one such possibility.

One conclusion of a more specific nature is possible, albeit a negative conclusion. The northbound trade in corn that became so important by the turn of the century was as yet insignificant. Such a conclusion is possible because any such corn (unless from Fiskerton or further west) will have paid 1s per ton at Kirkstead or Barlings locks. Since the total receipts at those locks was only £5-16-9d, we know that such shipments cannot have exceeded 117 tons in the year.

Financial Implications, and a Conspiracy Foiled

We noted at the start that the Navigation Commissioners spent £6800 on improvements. It was raised by mortgaging the tolls: issuing debentures secured on the toll income. They bore interest at 5%. Thus it required £340 per year to service them.

A run of figures for net income up to the 1780s exists in the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society Banks-Stanhope deposit[8]. These agree with the presented 1765 and 1775 accounts, so presumably derive from a full run of annual accounts. They show that 1775 was not abnormal. Up to 1775 the income had never amounted to as much as £340. From 1775 to 1785, it averaged about £340. Since there were continuing expenses, it follows that the navigation was running at a loss for the first two decades of its existence. How this loss was accommodated – whether by subvention from the Drainage Commissioners, or simply defaulting on a proportion of interest payments – is not apparent from the minutes.

For a scheme of this sort to face financial problems because the works had proved more costly than anticipated was all too common; but for revenue to fall short of what was anticipated is less frequent. Even as late as 19 Feb 1762, the intended tolls were stated to be 4d per ton at the Grand Sluice, 2d at every other lock; that would amount to just 10d/ton end-to-end[9]. At this date, the trade to Lincoln via the Fossdyke was running at about 20,000 tons/year. We know this from the Fossdyke toll receipts; these would not have been public at the time, but any of the Lincoln merchants could have estimated the figure from knowing the number of boats arriving and the average load of each. Langley Edwards is known to have estimated toll revenues at £375[10]. At first sight this seems a curiously precise figure, but I suggest that it was obtained by assuming that the Witham would capture half of Lincoln’s trade, and multiplying 10,000 tons by an average toll of 9d/ton.

The idea that the Witham might capture (or rather regain) half of Lincoln’s trade was probably widespread. John Grundy’s map setting out his plans for improving the river described the aim as Draining the said Fens and Low Grounds and restoring the Navigation of this River. That second phrase was doubtless understood by many to mean recovering the trade which Boston had lost.

There was, however, a problem. By far the biggest commodity handled was coal. When the Fossdyke had reopened in 1745, it was celebrated for reducing the price of coal in Lincoln from 21s per chaldron to 13s[11]. This fall was not so much a consequence of the Fossdyke improvements as of the introduction to the Trent valley of cheaper coal from Yorkshire – although Richard Ellison may well have had a hand in the latter as well as the former. No matter how brilliantly the Witham was improved, it would never be able to recapture the Lincoln coal market as long as the Fossdyke was bringing Yorkshire coal.

A small group of the Boston promoters seem to have understood this. They realised that the only way to restore the trade of Boston was to ruin the Fossdyke; what is more, they saw how this could be done.

Maintaining water levels in the Fossdyke in summer had always been a problem. The logical solution was a lock at Brayford Head in Lincoln to hold up the level there. Such a lock had been constructed in the 1670s but it had impeded drainage; the proprietor of Skellingthorpe had gone to law over the matter (after his tenants had taken direct action and been indicted for doing so). The lock gates had been taken away and were never replaced[12]. Richard Ellison had hoped to make such a lock unnecessary by excavating the bed of the Fossdyke but encountered running sands: any excavation simply filled in through slumping of the banks. The solution eventually found was a low dam at the Brayford Head, justified by the polite fiction that it was a ‘natural staunch’ or sand bar. There was little doubt that it was illegal, but the legal remedy required action by the Fossdyke Commissioners who in practice only met when summoned by the Lincoln Town Clerk. As long as the Corporation was happy with the ‘natural staunch’ nothing was going to happen, even though landowners, especially those in the vicinity of Torksey, had a justified grievance.

The Witham Bill as first drafted, gave the two sets of commissioners powers that extended from Boston up to Brayford Pool[13]. There was apparent logic in this from a navigation perspective, since the Fossdyke extended from Brayford Pool to Torksey; but it would have the side-effect of giving the new commissioners power to remove the ‘natural staunch’. If that ruined the Fossdyke as a side-effect, so much the better. Ellison was alert to the danger. Not only did he prepare a counter-petition against the Bill, he persuaded Lincoln Corporation and sundry Yorkshire boroughs to do likewise. With such opposition, the Bill was likely to fail and with it the fragile agreement that had taken a couple of decades to be reached. The navigation interests were a very junior partner to the drainage interests, for whom the exact upper limit of their powers was of no consequence. John Grundy was sent to Lincoln on a diplomatic mission. His brief was that the upper limit could be pulled back to Canwick Ings, even, downstream of Lincoln, if that would bring the parties together[14]. He spoke with, amongst others, Lord Monson, Messrs Nevile of Thorney and Amcotts of Kettlethorpe. It is the inclusion of these riparian landowners which makes it clear that the setting of Brayford Pool as the upper limit was no mere accident of drafting.

Grundy was able to resolve the conflict. The upper limit was pulled back to High Bridge, but it was agreed that Sincil Dyke should discharge above the Lincoln lock rather than below it, which had been Grundy’s original plan. (Ellison was concerned that the lower outfall would deprive the Fossdyke of water it needed from the Upper Witham.) The counter-petitions were still submitted but now merely as negotiating counters, to be withdrawn subject to the necessary changes being made to the Bill. From that resolution stemmed the financial weakness of the Witham Navigation.

The Sequel

The fortunes of the Navigation changed in the 1790s. Whether the cause was the French wars and the additional costs and risks of coastal shipping, or the growth of the corn-and-coal trade – fetching grain for the industrial north and taking coal as a return load – is unclear. Probably both causes contributed. At any rate, rather than Boston recapturing the trade of Lincoln, Boston itself was brought within the commercial networks of the Trent valley. Revenue on the Witham soared to heights unimagined in 1762, and the Navigation Commissioners became the dominant partner. But all that goes far beyond the records presented here.

Footnotes

[1] 2 Geo.III,c.32(L&P). For a fuller account see R C Wheeler (ed), Maps of the Witham Fens (LRS 96) 2008, 7-10[Back to text]

[2] LAO MON 7/17/63, LCL5051 p418.[Back to text]

[3] The Commissioners’ Minutes (TNA RAIL 885/1) record a decision 14 Oct 1766 that tolls in future were to be collected at Boston lock instead of Dogdyke.[Back to text]

[4] LAO 5LRA 1/136 (for 1765) and LRA 1/47 (for 1775)[Back to text]

[5] LAO 5LRA 1/135[Back to text]

[6] Certain names occur with different spellings, consistent within a single list but not between lists, suggesting that more than one clerk was involved.[Back to text]

[7] Minute of 13.7.1770.[Back to text]

[8] They are quoted in R Acton, The Financing and Operation of Mid-Lincolnshire Navigations, 1740-1830 (Sheffield MA thesis, 1971), of which there is a copy in Lincoln Central Library. [Back to text]

[9] LAO LCL 5051 p418[Back to text]

[10] LAO LD92: Observations on the Bill now Depending in Parliament for Draining certain Low Lands …[Back to text]

[11] Remarkable occurrences that have happened at Lincoln. (John Smith, printer, 1805) quoted in Lincs Chronicle 7.1.1887. There is a version of the original dated 1837 at LCL UP 421. In LAO LD 92 of 1762, it is stated that the coal price was halved, but this must be an exaggeration. An advertisement in the Stamford Mercury of 15 December 1743, by the Newark Boat Company offering Yorkshire coal for sale in Newark shows the extent to which Yorkshire coal was penetrating. [Back to text]

[12] RC Wheeler, “The Fossdyke Navigation 1670-1826”, Lincolnshire History & Archaeology, 49, (2017 for 2014) 47-8. [Back to text]

[13] LAO MON 7/10/33. The provision goes back to at least the Heads of a Bill agreed at a meeting at Sleaford, 23.11.1761, of which a copy is at LAO 2 ANC 10/4/1. [Back to text]

[14] He incorporated them into an account of the history of the Witham, which JS Padley had copied – now at LAO LCL5051 pp 418 et seq. [Back to text]